Olive Garden ads, prison cheesecake, and the surprising merits of the thick human skull

I’m adding something new this week. In my ongoing effort to evolve this newsletter into a podcast organically and deliberately, I’ve been thinking about how I might turn it in to a sort of multi-segment variety show where I interview the person closest to the banana. I have no idea if or how it would work, but to move one step closer, I’m offering questions at the end of each banana - the questions I’d want to ask after I had the person summarize the thing in question for you.

And this week, one banana grew far longer and riper than the others, so I’m going to place that last and offer you two smaller (though not necessarily lighter) ones up top.

Did they always play opera on Olive Garden ads? My friend @margarita did some painful legwork to trace the nature and character of ads for Olive Garden from the 1980’s to the mid-2000’s. This was the kind of thing I always hoped YouTube would facilitate when it first started to grow. Finally, we have a free, public, usable archive of the arcana or minutiae of the very building blocks of the psyches of most of us of a certain age - local, regional, and national tv programming and ads that we couldn’t skip. It was so ephemeral for so long, and now we can settle all kinds of bets and look back on what formed our glowing companion and social currency as kids.

Margarita helpfully summarized the look and content of the Olive Garden ads through the decades so you don’t have to watch any more than you’d like to, to get that macro view. In it, you can kind of see an arc from modernism to high modernism (think cubism), or is that high modernism to post-modernism - and then back to something more practical and direct.

Questions for Margarita: How did the argument about whether Opera is always in Olive Garden ads come up? What was at stake?

Update: I heard the following back from Margarita:

For your nightmare fuel:

Also a fun Twitter account to follow.

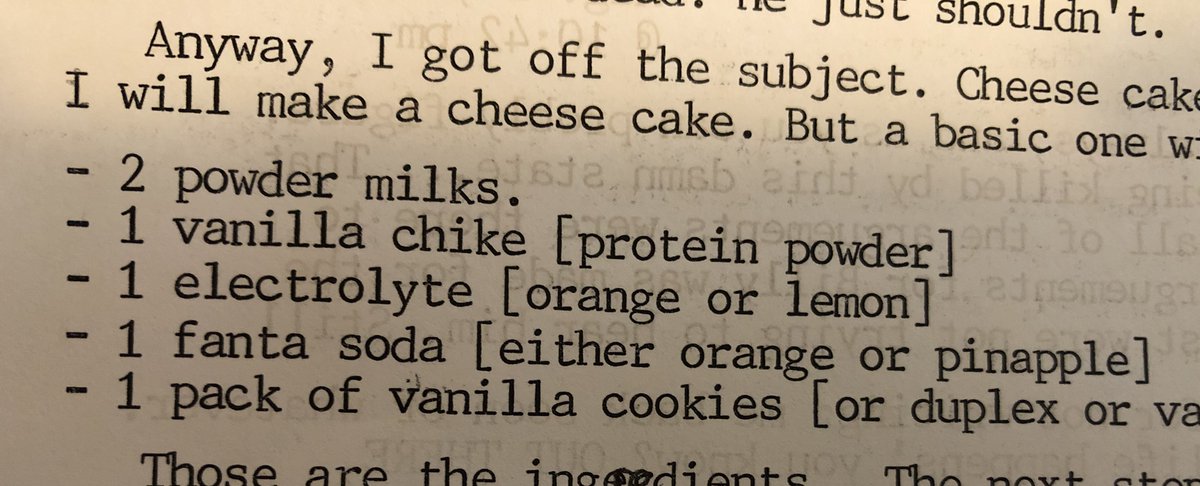

First, you take about 17 cookies and scrape out the filling. Keri Blakinger at the Marshall project shared a recipe for how to make cheesecake on death row in Texas, conveyed to her by a death row inmate who learned it from a friend on death row who was recently executed.

You should read this whole thread. I find it both deeply inspiring and deeply heartbreaking the way people can find ways to derive joy, even in the most dire of circumstances. I haven’t researched what these two folks are in for, it’s not necessary to know in order to make this observation. They’re people deprived of literally everything (an in fact, cell neighbors in solitary confinement) that manage to exercise their full humanity in the darkest moments.

Questions for Keri: How did this come up, in what context? What did you think and think about as you heard it explained? How did the quality of his voice sound as he took you through it?

Update: Keri read and replied as follows:

What you need to do, when you need to do it. That phrase sparked a memory as I read the sobering article from Paul Tullis at the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists titled “The brain-computer interface is coming and we are so not ready for it.”

That phrase sparked the memory of a phrase that was once the ubiquitous garbage phrase for some reason associated with what used to be called “domain squatter” pages: “What you need, when you need it.” Back in 2007, they used to look like this:

These were the detritus of the web, empty garbage pages that domain name squatters would throw up in the hopes that some dummy would mistake it for something useful or a gateway to nudes or something, and they’d use the search box or click and the squatter would make some affiliate dollars or lead the user to some kind of scam. I think it was also a search engine play, to get the earlier, more primitive search engines to think there’s something there.

At the time, my boss Ken and I pondered why that phrase was chosen. That phrase (you can see it just below Gongle.com) conveyed the promise of the web, and of start pages of the time, I guess. “Look, here, we’ve very carefully compiled exactly what’s most urgent to you at this very moment, and given it to you now, at the peak of its utility!”

So it was kind of amusing to come across a very similar phrase coming from the former head of Biological Technologies at DARPA, as a summation of the promise of a terrifying, world-changing technology that’s just about here: “Think of a universal neural interface you could put on and seamlessly interact with anything in your home environment, and it would just know what you need to do when you need to do it.”

We’ve come a long way with technology since 2007. As one example from the article, these interfaces can now see “the neural activity in the brain of a mouse that corresponds with its flicking its whisker.” And yet, it’s still a giant misdirection, no different from the domain squat page. Of course DARPA doesn’t want the ability to control things (including prosthetic limbs or your own broken limbs that have lost their utility) from/to a sensor connected your brain because it’s going to know and deliver things to your lazy ass as your desires arise. This technology is game changing for people who have lost use of their limbs, absolutely, and that’s how these grants got started. But the article mentions that out of the 1,650 Iraq and Afghanistan vets who lost limbs, only 8 have gotten new prosthetic systems out of it. The war-making capabilities are far more mind-blowing from a military-industrial standpoint and that’s why this stuff is being funded and evolved. Eventually in the article, one of the program leads explicitly states that.

If you’ve listened to the podcast or watched the show Homecoming recently, then there’s a wrinkle that might have popped in to your head. It’s not necessarily the idea of making a supersoldier who can control an exoskeleton, although that’s certainly part of this. It’s important to also think about how technologies can be inflicted on the marginalized, and signing your life away as a soldier is a hell of a marginalization as new technologies are developed, any number of comic book origin stories will tell you that. The topical idea that may have occurred to you is that this technology might allow the military to force wounded soldiers to keep fighting. Imagine an infantryman who is shellshocked and demoralized from sustaining severe shrapnel damage to his legs, but thanks to the interface in his brain, he’s able to keep moving those legs for as long as his brain or an external controller is functioning. The relentless Terminator of the near future might not be a robot; in fact it might be an unwitting soldier who signed away their consent to be used as a disembodied weapon when they enlisted.

If there’s one passage in the story that made me stop and marvel, it was one that came up when the author was discussing the three main barriers that research is focusing on right now. One of them is our big thick skulls. It turns out they work so well that you have to be able to get something past them to be able to read the neural lightning storm going on underneath. You can’t just put something on on top:

“But the human brain is reluctant to give up its secrets: People have these really thick skulls, which scatter light and electrical signals. The scattering properties make it difficult to aim either light or electricity at a specified area of the brain, or to pick up either of those signals from outside the skull.”

There’s something really interesting about that physiology forming a barrier to manipulation of our bodies through our brains. It probably won’t hold things off for much longer, but what does it mean about us and about this frontier, that this design that has allowed humans to thrive for a while now also keeps our grubby hands out of what we think we want to do next?

This is a page turner of a science article, and I had many more notes to share but I don’t want to go past these 7 or so grafs. I highly recommend you put some time aside to lose yourself in to it.

Questions for Paul: In what ways did researching this story affect your mood? Some of these revelations almost seem like tropes to a cynical reader at this point, only because we’ve seen this kind of pattern so many times before in history. What was most surprising to you?

Bonus banana: There’s no video, but there’s this fantastic story going around about a guy who successfully jumped a drawbridge in his car to escape the law. That last part didn’t work out, but…he did it! This is a huge leap forward for humanity. Here’s the best part of the write-up: “Drawbridge operator Andre Locke, who watched the wild scene unfold, recalled that “I looked, I said, ‘no, he ain’t.’” His disbelief quickly giving way to the realization that the man was, indeed, trying to jump the bridge, the worker hit an emergency stop button, but it was too late. “Over he went, blew out all four of his tires,” Locke said, “and then he crashed into the other gate.” While successfully completing such a jump may be cause for celebration in the movies, in this instance it led to the man being arrested since, with his car badly damaged, he was unable to flee the scene.”

Those are all the bananas I found for you this week. You can hit reply and it’ll go only to me. If you have feedback about the format tweaks or the slow, deliberate trudge towards podcasthood, I’m all ears. Thank you.